Review

by Theron Martin,Starting Point: 1979-1996

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Hayao Miyazaki is best-known for his wonderful, family-friendly movies, including the 2003 Academy Award winner Spirited Away, and for writing the epic Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind manga. Before he started focusing on those, though, he worked his way up through series animation projects. This collection of writings, which spans the period from his earliest animation efforts up through this preparations to make Princess Mononoke, examines his career, unique perspective on animation and life in general, and the projects he has been involved with using a mix of essays, interviews, speech transcripts, magazine articles, project proposals, and even scrapbook illustrations. |

|||

| Review: | |||

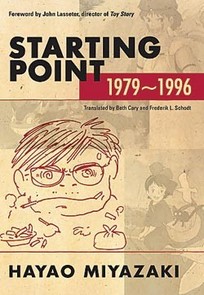

Though he would probably slough off such praise, Hayao Miyazaki unquestionably stands as one of the giants of animation, not just in Japan but worldwide; no less a figure that Pixar and Disney's John Lasseter admits in his Foreword to this book that Miyazaki's philosophies and works had a profound impact in shaping the changes which made Toy Story 2 into an even better work than its predecessor, and his work is widely-respected in the American animation community. This book may help a complete novice understand why. For anyone already familiar with Miyazaki's work, it tells you everything you could possibly want to know about Miyazaki the man and Miyazaki the professional. It is a must-read for any Miyazaki admirer. And my, does he certainly have a lot to say! Though he often complains of tight time schedules, Miyazaki apparently found considerable time over the years to jot down copious amounts of articles and essays and give a lot of formal speeches. Occasionally these writings ramble into random topics in much the same way that the Afterword comments manga-ka include in tankoubon releases do, but much more often Miyazaki knows exactly what he wants to say. By perusing these pieces, one can gain great insight into the philosophies he formed about both animation and life in general, philosophies which have had indelible impacts on all of his works. We also get to see the early circumstances and entertainment which influenced him towards becoming an animator. Perhaps most significantly, almost none of the pieces seem dated despite the fact that the earliest ones date back to 1979. The insights about the anime scenes which Miyazaki gleaned back in the late '70s and early '80s are still very much relevant today, such as how a comparative glut of anime series at the time was, in Miyazaki's view, lowering the quality of the work, trapping production crews in ridiculous time schedules which offered bleak pay, and making it more difficult for a work to seem special; as he puts it in 1982: ”We are living in a society that is wealthy yet poverty-stricken. We are able to listen to large amounts of music and watch large numbers of videos. But only a small fraction of these move us.” Would anyone dispute that these words are just as relevant today as they were 28 years ago? The first and meatiest of the book's five major sections focuses on what it means to be an animator. So much of this content is so relevant to the creative processes involved in animation that it should be excerpted from liberally in any textbook or guide book aimed at aspiring animators. Amongst major points, Miyazaki stresses the need for prospective animators to go out and experience the world before dedicating themselves to their craft, for only by garnering a broad range of experiences and observations can one understand how things work sufficiently to actually portray them in animation. He emphatically talks about how critical it is for even the most fantastic of animation settings to have a sense of realism – and by this he seems to mean “internal logic;” if the world created does not makes sense given the circumstances of the situation then the project will have a harder time connecting to, and thus being accepted by, the audience. Animation, in his mind, must also have a “purity of emotion,” a trait which can uplift and refresh the viewer, even if in a shallow sense; interestingly, he finds most Disney works decidedly lacking in this respect, claiming that they show “contempt for the audience.” Amongst other interesting observations he makes, he explains that running in animation must, for practical reasons, be portrayed very mechanically differently from what it is in real life, accuses anime of being prone to “overexpressionism,” and speculates that “the fascination with mecha is often stimulated by an unconscious orientation towards all things powerful and strong,” an observation which any mecha fan can probably appreciate if they think about it. He also, notably, stresses that he does not actively look to put ecological themes into his works (something he has often been accused of by detractors), primarily because he finds them too limiting and inorganic on their own. Working it in as just a piece of a bigger puzzle is, of course, another matter, as he definitely takes conservationism and a need to make at least some small contributions to cleaning up the environment To Heart; according to a story later in the book, the scene in Spirited Away where Chihiro leads an effort to pull a bicycle out of a river god's body is a close recreation of an incident from one of Miyazaki's own efforts in cleaning up a local riverbed. The second part deals with matters peripheral to anime, such as Miyazaki's reactions to certain films or commentary on the state of his country; he mentions, for instance, that one of the greatest challenges to survival in modern Japan is “to survive without being crushed to death by our repressive society." Much of this content is fairly random, making this the weakest section of the book. More interesting is the People section, where Miyazaki offers observations on various people he has met and worked with, including a story about the insane work ethic of one female finish inspector, how he regards Osamu Tezuka as a rival rather than idolizing him, and his amusing comments about colleague and fellow Studio Ghibli leader Isao Takahata's slothfulness. Following this section are several pages of Miyazaki illustrations – some in color on glossy pages – which include a comic history of early flight, design sketches for various planes and vehicles, and scrapbook ruminations. Possibly the most purely interesting part is the Planning Notes/Directorial Memoranda section, which provides proposals and planning memos for most of Miyazaki's major projects over the years, up through Princess Mononoke. Those who have seen Miyazaki's earlier films can delight in seeing how some of these projects changed in subtle or overt ways from initial planning to final product; Princess Mononoke, for instance, was originally intended to have a bear god as well as a wolf and boar god. (A later interview, though, reveals that the first concept that Miyazaki attached that name to was more of a pure Beauty and the Beast adaptation.) The last and longest section, Works, takes a more in-depth look at many of Miyazaki's major pre-PM titles, including Lupin III, Future Boy Conan, Laputa, My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki's Delivery Service, Porco Rosso, the more obscure earlier work Panda! Go, Panda! and of course Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which gets the most thorough treatment due to its combined film and manga discussions. These sections are almost entirely for those familiar with the respective titles, as they go into great detail about specifics of each title and only make the occasional general comments. Each of these sections offers substantial insight about Miyazaki's intent (or lack thereof) with each work, with the most important of these probably being his comments about forests in the Totoro section, as much of what he said about his perception of forests at that time later popped up again in Princess Mononoke. In addition to Lasseter's Foreword, this Viz Media publication also includes a substantial biographical chronology up-to-date through mid-2009 and an 11-page Afterword by Takahata. The translator team did a superb job in maintaining sensible English wording while still carrying through Miyazaki's distinctive style. The book comes in hardback form with a slipcover featuring a sketch of Miyazaki and screen shots from several of his works. The back cover flap carries a brief bio, which serves more for advertising purposes than for being informative. At 461 pages, Starting Point is not a quick read, and the density of its content assures that it is not a light one, either. This is not a book readers are likely to polish off over a slow weekend. The myriad sources it draws from results in some details and accounts getting repeated more often than they need to be and some sections will be of little or no interest to those who have not seen all of the relevant movies. The portrait it paints of Miyazaki is not always flattering, either; though these essays show Miyazaki as a man with a keen understanding of both animation and the minds of children, he laments that his work resulted in him barely being present for the rearing of his sons, and some details suggest that he was not always the easiest person to work with. However, so much of what he has to say is so eminently quotable that this review could be more than doubled in length just by including the best statements not included so far. Starting Point is worth the time and effort to read and is certainly a worthy addition to any anime fan's bookshelf. One need only have a respect for animation (and those who make it) to appreciate the insight it offers. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A-

Story : A-

Art : B

+ Enormously insightful, chock full of background details. |

|||

|

discuss this in the forum (12 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history |

|||