Review

by Cindy Sibilsky,| Review: | ||||||||

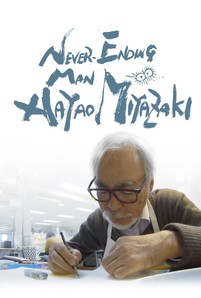

Animator, director and subject of Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki, is known for creating worlds of wonder — though not without a lot of blood, sweat and tears in the process. He and his cohorts at the Japanese animation Dream Factory, Studio Ghibli, have been crafting beloved anime classics for over three decades. Studio Ghibli films — particularly those by Miyazaki — possess not only the power to transport viewers to another universe, but they possess a transformative power. Many have pervasive themes of family dynamics, reverence for nature (and the grave consequences that arise from greed, vanity and hunger for power), the mysteries of the spirit world, embracing change and challenges and, in doing so, discovering your highest self. All the while they never shy away from weightier elements such as insecurities, fear, pain, loss and even death. But lest this make a Studio Ghibli film seem to dour or serious, one tends to end their encounter with their enchanted worlds feeling triumphant and uplifted. However, with the act of creation comes violent birthing pains, and few know those aggravations better than Hayao Miyazaki himself — an artist who is a notorious perfectionist with such meticulous and painstaking attention to detail that he has often upset or alienated those closest to him — staff, colleagues and even family members. It can be easy to idolize such a master for the brilliance of their work and put them on a pedestal (not unlike Walt Disney, who he has been compared to), but in reality these geniuses are flawed human beings with fears, egos and struggles just like the rest of us (many even moreso). Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki, the documentary produced by NHK and distributed in North America by GKIDS, is an attempt to portray the intimate day-to-day experiences from exuberant joy to irritated lamentations and grumblings of a man in his 70s who just can't seem to stop, despite many attempts and claims of retirement. Miyazaki and Ghibli have churned out multiple award-winning, globally renowned mega-hit films since 1984 — when his Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind debuted — demonstrating the lasting power of their creator's vision. So it was a disappointment to all when Miyazaki publicly announced his retirement at age seventy-two in 2013. “Studios devour people,” he commented in the documentary, with a snippet of the No-Face monster from Spirited Away gorging himself on other beings. Of course, this didn't last long. While settling down might seem like reasonable thing to do at such a time in one's life, especially after so much acclaim and success, the man with the imagination that created the iconic films and characters seen in My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away and many others, simply could not shake his burning desire to create. So in 2016, he set out on a new adventure — one that may, deceptively, appear to be a small undertaking for such a giant: a short animated film about an insect called Boro the Caterpillar.  In reality, this endeavor was so challenging and frustrating that it drove him to question his age, ability, and even his instincts, though it ultimately made him discover his deepest truth and passion again — that explosive urgency to express something meaningful that is so predominant in all of his creations. Never-Ending Man was shot and directed by Kaku Arakawa. At first it takes a moment to get used to the film's quality —it's sometimes shaky, dark or grainy, out of focus or shot in extreme close-ups and odd angles that gave it a bit of a Blair Witch Project feel at times — without the fear or drama of course (to the contrary, it is rare to witness a subject so much at ease). This may be due to the fact it is an NHK documentary. NHK is the only public national broadcasting TV network in Japan. Much like PBS, they produce a lot of humble and wholesome documentaries, many of them showcasing the Japanese countryside and small-town life with older people, older ways, and older customs. But the benefit of such a naturalistic style (once you got used to it) was that it gave the feeling of an old friend on an iPhone, following Miyazaki on his daily adventures and interactions in a way inaccessible to most. The two men have worked together repeatedly since Arakawa's first interview with him in 2005, so his guard was down and he appears to be more comfortable and open with the filmmaker than the new animation staff. Besides, no one is watching this for the cinematography — but rather for a glimpse behind the curtain to observe what goes on in the mind of such a master and see if the spark of inspiration can be reignited for an animation technique Miyazaki has famously dismissed. The project that lured him out of his life as a retiree also leads him into previously uncharted (and undesired) territories. Miyazaki's intention to create Boro, a curious caterpillar in an enchanted environment, made him aware of the limitations of his hand-drawn style, yet his unwavering need to bring this character to life (“Until he finishes Boro, he will feel incomplete,” remarked a colleague), forced him to cross over to a territory of technology he'd previously shunned: CGI. Though Studio Ghibli have been regarded as innovators, the production company and especially Miyazaki have always favored the old-fashioned way of hand-drawn animation. The first Ghibli film to incorporate computer graphics was Pom Poko (1994). Following that, the first Miyazaki feature to use computer graphics (for about 15 minutes) and the first Studio Ghibli film to use digital coloring was Princess Mononoke (1997). Then the very first Miyazaki feature-length film to be shot using a 100% digital process was the Academy Award-winning Spirited Away (2001). But Boro the Caterpillar is his first foray into CGI from start to finish (with the exception of partial storyboarding).  Miyazaki's disdain and distrust for computer-generated images are contrasted by his respect for the young artists he says “remind me of my old self,” and his intrigue with the process so different from his own. He watches in wonder as they translate and transform his drawings into a three-dimensional model and make it move on a computer monitor, though he can't help but criticize, “The middle hump should be higher when he runs and should create a ripple effect,” he commented, “I want to push them to the limits and see what CGI can do.” He is nothing if not a perfectionist with an eye for detail, which sets him apart from the other animators working on the short. Miyazaki focuses on the things that others have overlooked, such as the tiny hairs on the caterpillar (“Children will notice”) and especially Boro's birth into the world, remarking on a detail that might escape anyone else. “His head turns too fast, too much like an adult. He is a baby and babies are clueless and fresh to the world around them,” Miyazaki emphatically commented upon seeing a motion test rendered by a CG animator. These seemingly minute observations may seem asinine but they come together to create an end result that separates a true genius from a mere technician. He furiously draws out his ideas and explanations, providing a language comprehensible to all that the CGI animators marvel at. “It feels like we are making a film. It's exciting! My heart is racing!” he exudes, then shortly thereafter vents his frustrations regarding this newer, colder artform, “I think that CGI animators focus on the external, not the internal. All movement must have intent.” Wearing his signature white apron and chain-smoking (there is always a cigarette present, even if unlit), Miyazaki muses upon the deaths of several close co-workers, one who passed away at ninety-three who he had collaborated with for over 50 years. “People are dying who should have outlived me,” he reflects. Old age and mortality are recurring themes —topics that are not taboo in Japanese culture or NHK productions. Miyazaki constantly refers to himself as a “geezer” and notices how ancient and worn his same-aged peers appear (which he exploits by drawing them standing in a line for their licence renewals), but he looks to the youth for energy and vitality as well as the return to work, though his long-time Ghibli colleagues joke that while young people may invigorate him, he ages them. This is because of Miyazaki's fervent striving for perfection and yearning for truth and meaning, “We have to make something we are proud of -- a film that will amaze people,” he challenges the CGI artists, all the while questioning if the endeavor was even worthwhile and contemplating quitting it. Miyazaki makes something as simple as creating an animated short seem an epic and insurmountable ordeal. “Such a hassle!” is a catchphrase he utters regularly, though it is clear the hassle is what he lives for. “I set this battle upon myself. We have had no bloodshed yet. I must be brave and fight my desire to avoid a hassle.”  This eureka moment leads him into a renewed passion and fervor that reignites his magic spark to construct the world for Boro he sees fit — “We should add night fish! But they must be mysterious.” Voila! Inspiration strikes! The film then intercuts the famous scene from My Neighbor Totoro where Totoro aides the sisters in making their garden grow and seeds sprout into trees. Upon seeing the new azure creatures floating before Boro's eyes, he extolled, “What a bustling world of strange wonder!” Maybe it was the joy of working again, maybe it was the frustration, or maybe it was the next experience that pushed Miyazaki off the edge to make another unexpected announcement. Nobuo Kawakami, president of Kadokawa DWANGO media company and producer-in-training at Ghibli, informed him that they had been researching the modern CGI phenomenon of incorporating “deep learning,” where a computer imbued with A.I. will be able to draw or construct a CGI character with the same ability as a human. The seemingly crude demonstration of this, in the studio conference room, deeply disturbed Miyazaki. It showed a pathetic and loathsome being (initially without its head and then with one) crawling horrifically on all four limbs. Kawakami enthusiastically remarked upon its authentic composition and that it could be an excellent application in, say, a zombie game. Indeed, it was uncomfortably realistic and quite terrifying. But there was something more disturbing that Miyazaki picked up on and protested with the same kind of unshakable intensity as one of his heroes or heroines: He explained that he had a friend who was severely disabled and could hardly walk so that even giving an amiable high-five was a major challenge for him. This hollow 3D digital creature represented to Miyazaki a kind of disrespect to his neighbor, but also to all of humanity. “Who or whatever created this has no regard for human pain and suffering and I want nothing to do with it. This is an insult to life itself,” he declared as he walked out of the conference room, leaving Kawakami and fellow staff speechless. This was perhaps the most poignant moment in the film and the scene that best demonstrated Miyazaki's conviction despite his anger and annoyances at the process. It also served as an epiphany — “I feel the end of the world is near. Humans have lost confidence. Hand-drawing is the only answer. I won't run from it anymore.” With the decision made, he went to his long-time colleague Toshio Suzuki, former director/producer/president and current General Manager at Ghibli (while being filmed but none seemed to mind the Miyazaki approved and allocated spy) and asked, “Shall we do it? Shall we make a feature film?” The answer was, of course as we now know — “yes” — though not immediately when it was pitched in 2016 at the time of this documentary but he began the storyboards anyhow. Nothing can halt this man when he's on a mission. The famously detail-oriented “never-ending man” is fully aware that his next film entitled How Do You Live?, based on Genzaburō Yoshino's 1937 novel about the spiritual journey of a fifteen-year-old boy after the death of his father, may take years to complete (though in the documentary they planned it to be released before the Tokyo Olympics in 2020, it has become clear it will be a longer process than they ambitiously expected). As he laughed about having not told his wife yet, Miyazaki expressed that the prospect of this new feature film gave him something to live for, though it also further frustrates and enlivens him in tandem — constantly recurring themes in his life and work. The film ends abruptly with that sentiment — on a cliffhanger — without showing any completed scenes of Boro the Caterpillar (it debuted at the Studio Ghibli museum in March 2018, and the company is famously hesitant to show Ghibli Museum Shorts outside of the theater on property grounds) or the aforementioned feature-to-be. Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki often feels fragmented, but perhaps it is just as well. Much of it was more like being a fly on the wall, privy to private moments and normally closed conversations. The film is an intimate documentation of daily activities while attempting to shed a shard of light on the famously complicated and contrarian visionary in the autumn years of his life as he explores the last attempts at his legacy. |

||||||||

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : B-

+ An intimate glimpse inside the process of a legend in the twilight of his career. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (5 posts) | | |||